When it comes to the legality of web scraping, everyone wants a simple yes or no. The short answer is: yes, scraping publicly available data is generally legal in the United States. But hold on—this isn't a free pass to scrape anything and everything. The reality is a complex legal landscape where how you scrape, what you scrape, and what you do with that data matter immensely.

For developers and businesses, the problem is clear: how do you gather the public data you need for market research, price monitoring, or AI model training without crossing legal and ethical lines? Ignoring these rules can lead to cease and desist letters, costly lawsuits, and permanent IP bans.

This guide tackles that problem head-on. We'll explore different approaches to data gathering, from manual collection to sophisticated scraping APIs, and provide a step-by-step framework for building a legally compliant and technically robust scraping strategy.

A Straightforward Answer to a Complex Question

There's a common myth floating around that web scraping is inherently shady or illegal. That’s just not true. At its core, automated data collection isn't against the law. Think of it like taking a photo in a public park; it's perfectly fine. But if you sneak into a private building and start snapping pictures after ignoring a "No Photography" sign, you've crossed a line. Web scraping operates on a very similar principle.

The legal landscape here is shaped more by court rulings than by specific laws written to ban scraping. This means the "rules of the road" are constantly being defined by how judges interpret existing laws in the context of new technology. For any developer or business in this space, understanding these interpretations is absolutely essential.

Key Factors Determining Legality

So, what separates a legitimate scraping project from one that could land you in hot water? It usually boils down to a few core factors:

- Public vs. Private Data: Is the information you want openly accessible to anyone on the internet, or is it locked behind a login or paywall? Scraping data that requires authentication is a huge red flag and carries significant legal risk.

- Terms of Service (ToS): Did you check the website's rules? If its ToS explicitly forbids automated access or scraping, ignoring it can lead to claims of breach of contract.

- Copyrighted Material: Are you copying creative works like articles, photographs, or videos? While raw facts can't be copyrighted, the unique way they are presented often can be.

- Server Impact: Is your scraper hammering the website's servers and slowing them down for everyone else? Overly aggressive scraping can be seen as "trespass to chattels," which is a legal term for interfering with someone else's property.

To give you a clearer picture, I've put together a table that breaks down the main legal considerations we'll be diving into. This framework is crucial whether you're building your own scripts or using professional web scrapers.

Key Legal Considerations for Web Scraping

| Legal Consideration | What It Governs | Key Takeaway for Scrapers |

|---|---|---|

| Computer Fraud & Abuse Act (CFAA) | "Unauthorized access" to computer systems. | Primarily applies to data behind logins; public data is generally safe. |

| Terms of Service (ToS) | The contractual agreement between a site and its users. | Violating a clear anti-scraping clause can result in legal action. |

| Copyright Law (DMCA) | Protection of original creative works. | Avoid scraping and republishing copyrighted content like articles or images. |

| Trespass to Chattels | Interference with another person's property. | Scrape at a reasonable rate to avoid overloading the target website's servers. |

Think of these four pillars as your legal compass. Keep them in mind, and you'll be well-equipped to navigate the complexities of data scraping responsibly.

Understanding the CFAA: The Anti-Hacking Law at the Center of the Scraping Debate

When you dig into the legal battles over web scraping in the United States, you’ll find one law at the heart of nearly every single one: the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). This is a big deal, because the CFAA was originally passed way back in 1986 to fight computer hacking—long before anyone was thinking about modern data collection. This mismatch has sparked a decades-long fight over whether it even applies to web scraping.

The whole issue boils down to a simple but powerful phrase in the law: "unauthorized access." In plain English, the CFAA makes it a crime to access a computer without permission. To get your head around this, think about the difference between a public library and a private, locked archive.

When you walk into a public library, you're welcome to browse the shelves, read any book you find, and jot down notes. This is exactly like scraping publicly available data from a website. The information is out in the open for everyone, so no special permission is needed. This is what we call "authorized access."

What Counts as a Locked Door Online?

Now, let's go back to that library. Imagine there's a special section for rare manuscripts kept behind a heavy, locked door. If you were to pick that lock or sneak past a guard to get inside, you've clearly crossed a line. That’s precisely the kind of digital trespassing the CFAA was built to prevent—bypassing security measures to get at private, protected information.

This distinction is the key to understanding the whole CFAA and web scraping mess. The legal question that keeps coming up is, what really counts as a "locked door" on the internet?

- Password-Protected Areas: This one is pretty obvious. Any data sitting behind a login screen is clearly meant to be private. Using a scraper to access it, especially with stolen credentials or by creating fake accounts against the site's rules, is a classic CFAA violation.

- IP Blocks and CAPTCHAs: Websites throw up technical barriers like IP blocking and CAPTCHAs to manage automated traffic. While getting around these isn't the same as cracking a password, some companies have argued it's a signal that your access is no longer welcome or "authorized."

- Cease and Desist Letters: This is a big one. If a company sends you a formal letter telling you to stop scraping their site, and you keep doing it anyway, your actions can be seen as knowingly accessing their servers without permission.

The CFAA's real power comes from its age and ambiguity. It was written before the web as we know it even existed, forcing courts to try and fit old rules to new technology. This has led to a history of conflicting decisions.

The legal ground here is constantly shifting, shaped by one landmark lawsuit after another. While the CFAA was made to stop hackers, its use against scraping hinges entirely on how courts interpret "unauthorized access." For a while, things looked bad for scrapers. In early cases like Facebook v. Power Ventures, courts sided with the big companies, ruling that violating a site's terms of service while scraping could lead to massive fines. If you want to dive deeper, you can explore the history of key web scraping lawsuits and see how these interpretations have evolved.

The Tide Turns: The Rise of Public Data Access

More recently, we've seen a dramatic shift, thanks in large part to the groundbreaking LinkedIn v. hiQ Labs case. In 2022, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals delivered a ruling that changed the game: scraping data that is publicly available does not violate the CFAA.

The court’s reasoning was refreshingly simple. You can't be a trespasser in a public park. If data is visible to anyone online without needing a password, then the "door" isn't locked. Therefore, using a scraper to collect it doesn't count as "unauthorized access" under the CFAA.

This decision was a massive win for data scientists, researchers, and any business that relies on public data. It set a powerful precedent, making it clear that the CFAA isn't a weapon for companies to claim a monopoly over public information. But don't get too comfortable—the CFAA is still very much a risk if you’re scraping private data or using aggressive methods that could harm a website's servers.

Looking Beyond the CFAA: The Real Legal Minefield

While the CFAA gets all the media attention, focusing on it exclusively is a bit like watching a football game by only following the quarterback. You miss the rest of the action.

The truth is, companies rarely attack scrapers from just one angle. They usually throw everything they can at you, and understanding these other legal claims is absolutely essential for navigating the legality of web scraping.

Even if your scraper is perfectly CFAA-compliant, you could still find yourself in serious trouble. Let's break down the three most common claims you're likely to run into.

Breach of Contract and Terms of Service

This is the low-hanging fruit for any company looking to shut down a scraper. A website's Terms of Service (ToS) is, for all intents and purposes, a legal contract between the site owner and you, the user. If that contract explicitly bans automated data collection—and many do—then scraping is a direct violation.

Think of it like getting a membership to a private club. When you sign up, you agree to follow the house rules. If a sign on the wall says "no running" and you start sprinting through the halls, the club can kick you out. By using a website, you are agreeing to its ToS, whether you've read them or not.

The strength of this claim often boils down to how you "agreed" to the terms:

- Clickwrap Agreements: These are the strongest. You had to physically check a box or click "I Agree" during signup. It's tough to argue you didn't know about the rules.

- Browsewrap Agreements: These are much weaker. The ToS is just a link buried in the site's footer. Courts are often skeptical that users even knew a contract existed.

Either way, knowingly ignoring a ToS is a huge risk. It clearly shows you intended to disregard the site's rules, which never looks good.

Copyright Infringement Under the DMCA

Copyright law is designed to protect original creative works—articles, photographs, videos, and even the unique way a database is structured and presented.

While raw, unadorned facts (like a stock price or a product's weight) can't be copyrighted, the creative expression of those facts absolutely can be. If you scrape and republish a news article, a well-written product description, or a gallery of professional photos, you could easily be infringing on the site owner’s copyright.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) adds another serious layer to this. It was specifically created to protect digital content, and its "anti-circumvention" rules make it illegal to bypass any technical measure put in place to protect that content.

While simply ignoring a

robots.txtfile isn't a crime in itself, it's often used as powerful evidence in court. It demonstrates that you were aware of the website's rules for automated access and consciously chose to ignore them, which can dramatically strengthen a company’s case against you.

And don't think borders will protect you. Web scraping is a global game, and laws can have a surprisingly long reach. Courts have shown that U.S. laws like the CFAA and DMCA can apply even when neither party is based in the United States. This is becoming even more critical as scraped data is increasingly used to train AI models, a whole new frontier for legal challenges. To really get a handle on these global issues, you can delve into the complexities of international web scraping law.

Trespass to Chattels

This one sounds ancient, because it is. "Chattels" is just an old legal term for personal property. Trespass to chattels means interfering with someone's property without their permission.

How does this apply to web scraping? The claim arises when a scraper sends so many requests that it overloads a website's server, slowing it down for legitimate users or even causing it to crash.

Imagine someone sending thousands of junk letters to your mailbox every single day, making it impossible for you to get your real mail. That’s the digital equivalent. An overly aggressive scraper that harms a server's performance is seen as directly interfering with the company's "property." This is exactly why responsible scraping practices—like rate limiting your requests and scraping during off-peak hours—aren't just polite. They are a critical legal defense.

How Landmark Court Cases Shaped the Rules of Web Scraping

While laws like the CFAA give us a starting point, the real-world rules for web scraping are hammered out in the courtroom. It’s only when these abstract legal ideas get tested by real lawsuits that they become the practical guidelines we follow today. If you're serious about scraping, you absolutely have to understand these landmark cases, because their outcomes directly define what you can and can't do.

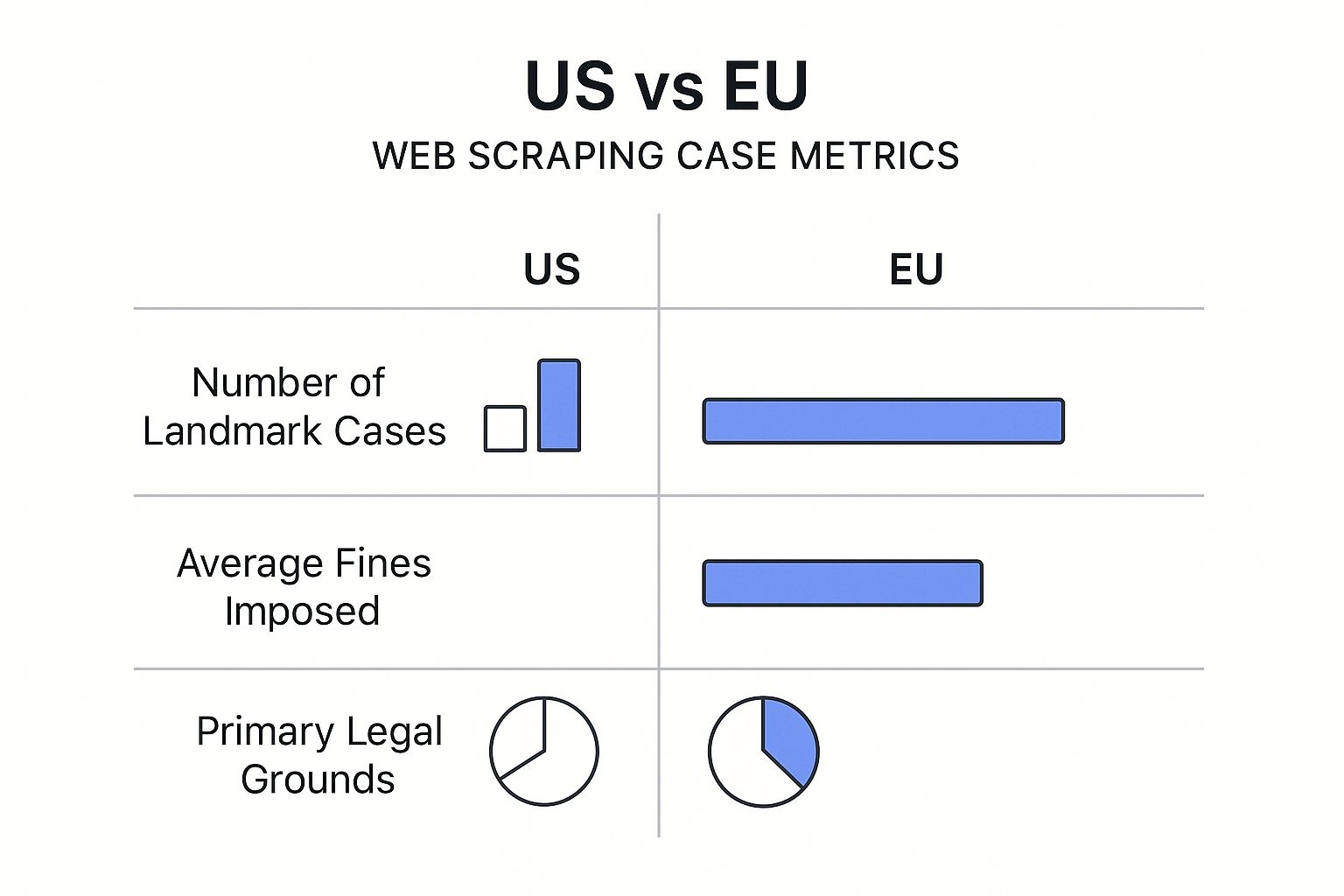

This infographic gives you a bird's-eye view of how the legal fights in the US and EU differ, highlighting the number of major cases and what they were fought over.

As you can see, the US has seen far more precedent-setting battles, most of which hinge on the CFAA. In the EU, the conversation is more often about GDPR and database rights. Let's dive into the stories behind the US lawsuits that changed everything.

LinkedIn vs. hiQ Labs: The Public Data Watershed Moment

The clash between LinkedIn and the analytics firm hiQ Labs is, without a doubt, the most important web scraping case so far. For years, hiQ scraped public LinkedIn profiles to create tools that analyzed employee attrition risk. LinkedIn knew about it and didn't care—until they decided they did. They sent hiQ a cease and desist letter and cut off their access.

Instead of backing down, hiQ took LinkedIn to court. Their argument was simple: LinkedIn couldn't use the CFAA to gatekeep data that was available for anyone on the internet to see. The case went all the way up to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ultimately sided with hiQ.

The court's reasoning was refreshingly straightforward. Accessing a public website isn't "unauthorized access." The CFAA was written to stop digital breaking and entering, not to prevent someone from looking at information left out on a public sidewalk.

This was a massive win for data accessibility. It set a powerful precedent that the CFAA can’t be weaponized to create a monopoly over public information. For anyone scraping data, the message was clear: collecting data that isn’t behind a login or paywall is generally fair game under this crucial federal law. Grasping this case is vital if you're building something like a custom LinkedIn profile scraper.

Facebook vs. Power Ventures: A Cautionary Tale

Long before hiQ’s victory, the legal winds blew in a very different direction. The 2009 case of Facebook v. Power Ventures is a stark reminder of what can happen when you ignore a website's Terms of Service (ToS).

Power Ventures built a service that pulled together a user's social media feeds, including from Facebook. To do this, they scraped data after users gave them their Facebook login details. Facebook sent a cease and desist letter and started blocking Power Ventures' IP addresses. Power Ventures just found new IPs and kept going.

The court didn't just side with Facebook; it found Power Ventures liable for violating the CFAA. The key finding was that once Facebook explicitly said "stop"—first with the letter, then with the IP blocks—any further access was "unauthorized." This case established that ignoring a direct order to cease and desist can turn what might have been permissible scraping into a federal crime.

Craigslist vs. 3Taps: The Power of an IP Block

The fight between Craigslist and 3Taps drilled down on the legal weight of technical defenses. 3Taps, a data company, was scraping real estate listings from Craigslist and re-posting them. Craigslist fought back by blocking 3Taps' IP addresses and, like Facebook, sent a cease and desist letter.

And just like Power Ventures, 3Taps tried to play a game of technical whack-a-mole, using different IP addresses and proxies to get around the block. Craigslist sued, and the court ruled that 3Taps’ circumvention tactics were a clear CFAA violation.

This case reinforced a critical legal line in the sand: when a website takes explicit technical measures to block you, continuing to access it is unauthorized access. An IP block is the digital equivalent of a "No Trespassing" sign. Ignoring it isn't just a technical puzzle; it’s a legally meaningful act that proves you know you’re not welcome.

These cases didn't happen in isolation. They build on each other, creating the legal landscape we operate in now. To make it even clearer, let's break down the key takeaways from each legal battle side-by-side.

Comparison of Landmark Web Scraping Court Cases

Here’s a quick summary of these pivotal court decisions and what they mean for anyone involved in web scraping today.

| Case Name | Core Legal Issue | Court's Ruling | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|

| LinkedIn vs. hiQ Labs | CFAA and public data access | Scraping public data is not a CFAA violation. | The CFAA doesn't cover info that's openly accessible without needing a password. |

| Facebook vs. Power Ventures | ToS, cease and desist letters | Continued access after a C&D letter is unauthorized. | A formal letter officially revokes permission, making more scraping a CFAA violation. |

| Craigslist vs. 3Taps | IP blocking and circumvention | Bypassing an IP block is considered unauthorized access. | Technical blocking is a clear signal that your authorization to access is gone. |

Each ruling adds another layer of nuance, moving from the broad principle of public data access to the specific actions—like ignoring a letter or circumventing a block—that can get you into serious legal trouble.

Your Practical Checklist for Compliant Web Scraping

Understanding the court cases is one thing, but it’s time to put that knowledge into practice. The best defense against legal trouble is to build a process around compliance and being a good citizen of the web.

Think of this as your pre-flight checklist before launching any scraping project. Running through these steps can minimize your legal exposure and help ensure your data collection is responsible from the get-go.

Pre-Launch Legal and Ethical Review

Before you write a single line of code, the first move is always to do your homework and show some respect for the site you're targeting. This initial due diligence can head off the most common legal headaches before they even start.

-

Read the Terms of Service (ToS) First stop: find and actually read the website's ToS. Be on the lookout for specific clauses mentioning "automated access," "scraping," "crawling," or "data mining." If there's an explicit ban on scraping in a clickwrap agreement (the kind you agree to when signing up), that's a massive red flag for a potential breach of contract claim.

-

Always Check the

robots.txtFile This simple text file, located atdomain.com/robots.txt, is the webmaster's official instruction manual for bots. While it's not legally binding in the U.S., ignoring aDisallowrule is often used in court to demonstrate that you knowingly disregarded the site owner's wishes. In the EU, it can also serve as a machine-readable way for a site to opt out of data mining under copyright law. -

Scrape Only Publicly Available Data This is the bright line drawn by the LinkedIn v. hiQ Labs case. Never, ever scrape data that requires a login, password, or any other kind of authentication. Trying to bypass these barriers puts you squarely in the crosshairs of the CFAA.

Technical Best Practices for Good Citizenship

Once you've cleared the initial legal checks, how you scrape is just as important as what you scrape. Aggressive or sloppy scraping can hammer a website's servers, which can lead to "trespass to chattels" claims and paint a huge target on your back.

Being a "good citizen" of the web isn't just about ethics; it's a powerful legal defense. Demonstrating that you took steps to minimize your impact on a website's infrastructure shows a lack of malicious intent, which can be critical in any legal dispute.

Here are the technical rules to live by:

-

Identify Yourself with a Clear User-Agent Your scraper should send a User-Agent string in its request headers that clearly identifies who you are or what your project is about. Something like

"MyCoolProjectBot/1.0 (+http://myprojectwebsite.com)"is transparent and gives the site owner a way to contact you if there's a problem. -

Scrape at a Respectful Rate Don't bombard a server with rapid-fire requests. This is amateur hour. You need to implement delays (like

time.sleep()in Python) between your requests to mimic human browsing speed. Aim for one request every few seconds, not several per second. -

Scrape During Off-Peak Hours Whenever you can, schedule your scrapers to run late at night or over the weekend when the website's traffic is at its lowest. This minimizes your impact on real users and reduces the odds of you accidentally overloading the server.

-

Never Replicate an Entire Database Focus your scraping on the specific data points you actually need. Avoid the temptation to download and republish entire datasets, especially if they represent a huge investment by the site owner. This is particularly critical in the EU, where database rights offer an extra layer of protection.

Data Usage and Post-Scraping Compliance

Finally, what you do with the data matters just as much as how you collected it. The legal risks don't vanish once your scraper finishes its run.

-

Avoid Competing Directly with the Source Using scraped data to build a product that directly competes with the original website is just asking for a lawsuit. The "fair use" doctrine in copyright law often hinges on whether your use is transformative—meaning you're creating something new—rather than just repackaging someone else's work.

-

Handle Personal Data with Extreme Caution If you collect any information that could be linked back to an individual (names, emails, user IDs), you're stepping into the world of privacy laws like GDPR and CCPA. These regulations have very strict rules about data collection, storage, and usage. Unless you have a clear legal basis, the safest bet is to avoid scraping personal data altogether.

By following this checklist, you build a strong foundation for ethical and legally defensible web scraping. For more advanced techniques, check out our guide on how to scrape without getting blocked, which dives into topics like rotating proxies and managing headers.

Practical Example: Using the Olostep API for Compliant Scraping

To illustrate how to apply these principles, let's walk through a practical example using Python and the Olostep API. This approach offloads the complexities of managing proxies, headers, and anti-bot systems, allowing you to focus on the data itself.

Here is a complete, copy-pasteable Python script that scrapes product information from a fictional e-commerce site. It includes error handling, retries, and respects ethical guidelines.

import requests

import time

import os

import json

# Your Olostep API key should be stored as an environment variable

# for security. Never hardcode it in your script.

API_KEY = os.getenv("OLOSTEP_API_KEY")

API_URL = "https://api.olostep.com/v1/scrapes"

if not API_KEY:

raise ValueError("OLOSTEP_API_KEY environment variable not set.")

def scrape_product_page(product_url):

"""

Scrapes a single product page using the Olostep API with retries.

"""

headers = {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"x-api-key": API_KEY

}

# Define the payload for the Olostep API.

# We are asking for the full HTML content of the page.

payload = {

"url": product_url

}

# Implement a simple retry mechanism for robustness.

max_retries = 3

for attempt in range(max_retries):

try:

print(f"Attempt {attempt + 1}: Scraping {product_url}")

# Make the POST request to the Olostep API

response = requests.post(API_URL, headers=headers, json=payload, timeout=30)

# Check for successful response from the Olostep API itself

response.raise_for_status() # Raises an HTTPError for bad responses (4xx or 5xx)

# The Olostep API returns a JSON object.

# The actual scraped page content is in the 'data' key.

# The 'metadata' contains info like the status code from the target site.

result = response.json()

# Check the status code from the target website

target_status_code = result.get("metadata", {}).get("statusCode")

if target_status_code != 200:

print(f"Warning: Target site returned status {target_status_code} for {product_url}")

# Depending on the status, you might want to retry or skip

# 404: Skip, 403/429: Retry, 5xx: Retry

if target_status_code in [403, 429, 503]:

# Wait longer before retrying for rate-limiting errors

time.sleep(5 * (attempt + 1))

continue # Go to the next attempt

else:

return None # Non-retriable error

# Return the HTML content of the scraped page

return result.get("data")

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"An error occurred on attempt {attempt + 1}: {e}")

if attempt < max_retries - 1:

# Exponential backoff: wait longer after each failed attempt

sleep_time = 2 ** attempt

print(f"Retrying in {sleep_time} seconds...")

time.sleep(sleep_time)

else:

print("Max retries reached. Failed to scrape the URL.")

return None

return None

if __name__ == "__main__":

target_url = "https://example-ecommerce.com/products/widget-pro-123"

html_content = scrape_product_page(target_url)

if html_content:

print("\nSuccessfully retrieved HTML content.")

# Here, you would parse the HTML using a library like BeautifulSoup

# For demonstration, we'll just print a snippet.

print("--- HTML Snippet ---")

print(html_content[:500])

print("--------------------")

# Example Response Payload from Olostep API:

# {

# "success": true,

# "data": "<!DOCTYPE html><html><head>...",

# "metadata": {

# "url": "https://example-ecommerce.com/products/widget-pro-123",

# "statusCode": 200,

# "headers": { ... },

# "latency": 1250

# },

# "usage": {

# "credits": 1

# }

# }

else:

print(f"\nFailed to retrieve content for {target_url}.")Troubleshooting Common Failures

When scraping, things will inevitably go wrong. Here’s how to handle common issues:

- CAPTCHAs: Services like Olostep often have CAPTCHA-solving capabilities built-in. If you're building your own scraper, this is a major hurdle. You might need to integrate third-party CAPTCHA-solving services, but be aware this can significantly increase complexity and cost.

- 403 Forbidden / 429 Too Many Requests: These are clear signals that you've been rate-limited or blocked. This is where a professional scraping API shines, as it automatically rotates through a massive pool of residential and datacenter proxies to avoid these blocks. If doing it yourself, you need to slow down, implement exponential backoff, and manage your own proxy pool.

- 5xx Server Errors: These indicate a problem on the target website's end. Your script should be built to handle these gracefully, typically by waiting a few minutes and then retrying the request.

- Timeouts: A

requests.exceptions.Timeouterror means the server didn't respond in time. This can be due to network issues or an overloaded server. The solution is to increase your request timeout and implement a retry strategy.

Comparing Alternatives

Olostep is one of several powerful scraping APIs available. A fair comparison requires looking at features, pricing, and ease of use.

| Service | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Olostep | Simple API, pay-as-you-go credits, built-in parsers, JavaScript rendering. | Startups and developers looking for a straightforward, scalable solution without complex subscriptions. |

| ScrapingBee | JavaScript rendering, residential proxies, Google search scraping. | Users who need to scrape modern, JavaScript-heavy websites. |

| Bright Data | Massive proxy network, web unlocker, SERP API, comprehensive dataset offerings. | Enterprises with large-scale data acquisition needs and complex requirements. |

| ScraperAPI | Handles proxies, browsers, and CAPTCHAs with a simple API call. | Developers who want a simple, all-in-one solution for common scraping challenges. |

| Scrapfly | Anti-scraping protection bypass, Python SDK, residential proxies. | Python developers who want fine-grained control and advanced anti-bot features. |

What to Do When You Get a Cease and Desist Letter

It’s a moment that can make your stomach drop: a cease and desist (C&D) letter lands in your inbox. With its official letterhead and stern legal language, it’s designed to be intimidating. But the absolute worst thing you can do right now is panic or, even worse, ignore it.

A calm, methodical response is your best path forward.

Your first move needs to be immediate and decisive: stop all scraping activity on the website in question. Full stop. This is a critical step that shows good faith and can instantly de-escalate the situation. Continuing to scrape after getting a C&D notice could turn a civil complaint into a potential violation of the CFAA, as we saw in the Facebook v. Power Ventures case.

Your Immediate Action Plan

Once you've halted the scraper, it's time to get organized and call in the professionals. This isn't a DIY situation; you need a strategic response.

-

Document Everything: Save a copy of the letter and any other communication you've had. Then, gather all your logs and records for that specific site—think dates, data collection rates, and the specific endpoints you were hitting. Your lawyer will thank you for this later.

-

Consult a Lawyer (Immediately): Do not try to write a response yourself. Find a lawyer with direct experience in internet law, intellectual property, and ideally, the CFAA. They're the only ones qualified to dissect the claims, whether it’s for breach of contract, copyright issues, or unauthorized access.

It is critical to understand that this guide is not a substitute for professional legal advice. A C&D letter is a formal legal action, and your response should be guided by a qualified attorney who can analyze the specifics of your situation.

Assessing the Threat Level

Your lawyer will help you read between the lines and figure out just how serious the claims are. They’ll look at the sender's legal grounds, the strength of their arguments, and what the potential risks are for you.

From there, you can work together to craft a professional response. Approaching this calmly and professionally from the start is your strongest initial defense.

Final Checklist and Next Steps

Navigating the legality of web scraping requires a blend of legal awareness and technical diligence. Here's a concise checklist to guide your projects:

- [ ] Review

robots.txtand Terms of Service: Always check the site's rules first. - [ ] Scrape Public Data Only: Never cross a login or paywall.

- [ ] Identify Your Bot: Use a descriptive

User-Agentstring. - [ ] Be Respectful: Scrape at a slow, human-like rate and during off-peak hours.

- [ ] Use Data Responsibly: Avoid republishing copyrighted content or competing directly with the source.

- [ ] Handle Errors Gracefully: Implement retries with exponential backoff for network and server errors.

- [ ] Stop Immediately if Asked: If you receive a C&D letter, cease all activity and consult a lawyer.

By internalizing these principles, you can build powerful data pipelines while minimizing legal risk and contributing to a healthier, more respectful web ecosystem.

Ready to collect web data without the legal guesswork? The Olostep API handles the complexities of ethical and efficient data extraction, letting you focus on building great products. Start your project with 500 free credits today by visiting https://www.olostep.com.